Breakout Artist and Activist

Painter, aspiring lawyer and immigrant activist Murphy Yanbing Chen ’21 harnesses the power of art and law to transform and inspire.

An oil painting in the Fine Arts Gallery depicts a woman and child burdened beneath the weight of all their belongings. Its color palette is dark, but a mysterious glow illuminates the two figures, banishing the shadows to the corners of the frame.

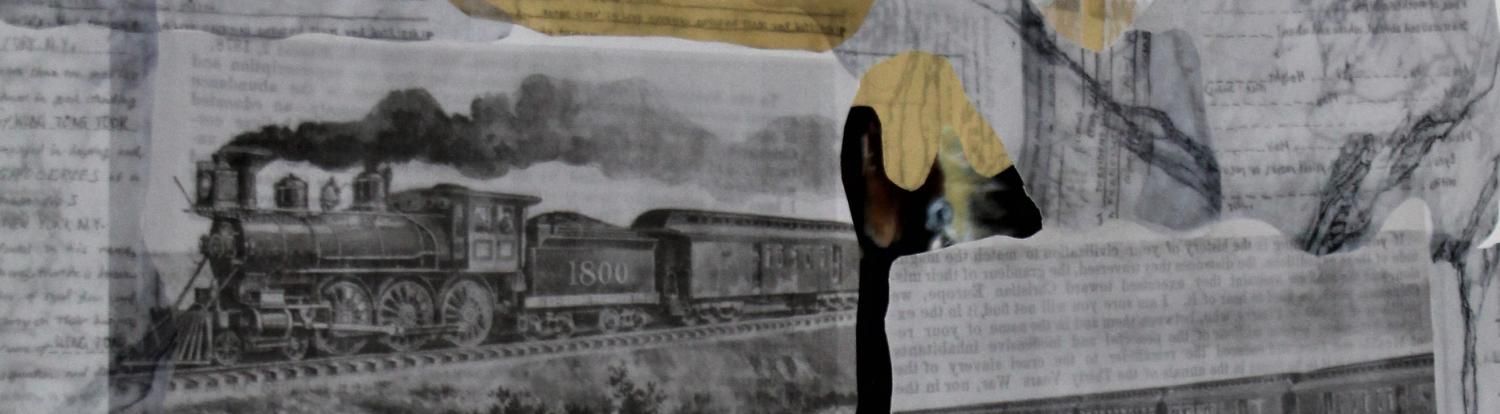

Overhead, a mobile-like assemblage of transparent vellum hangs from the ceiling. The tracing paper is covered with a montage of railroad maps, images of trains, the words “at home” and “homeless,” and the identification and deportation documents of Chinese laborers who worked on the American railroads in the 19th century.

The vellum is light and opaque, while the painting’s dark hues and heavy-laden subjects feel far weightier. But the two are linked in their depiction of life as an immigrant or part of a diaspora, says “Murphy” Yanbing Chen ’21, an Art major who created the installation for her senior exhibition. The project also has an autobiographical element.

“All works are essentially self-portrait,” she says. “These works are all related to my experience as a migrant and as somebody who kind of came out of nothing.”

Chen grew up in poverty in Yunnan Province in southwestern China. Her mother and her father are partial ethnic minorities, Jingpo and Mongolian people, who concentrated near the border with Myanmar. As a child, Chen often stayed with her grandmother while her mother earned a law degree to improve the family’s condition. Chen’s grandmother taught her how to draw, and her mother sometimes took her to a children’s art studio, where she experimented with acrylic painting.

Chen took an art history course before coming to the United States and initially applied to East Coast liberal arts colleges to continue studying art and art history. Deferring her acceptance, she decided to stay with family friends in Alpine, Texas, for a year and establish her own painting studio.

In Alpine, Chen immersed herself in the gallery scene and, for academic credit, became an exhibition assistant at the Chinati Foundation in nearby Marfa. She took more art history courses at Sul Ross State University and, for the first time, studied oil painting.

After realizing that Texas offered as many opportunities as the East Coast, she transferred to St. Edward’s in January 2019. In Associate Professor of Art History Mary K. Brantl’s classes, Chen encountered the idea that all artworks are more than simply aesthetic endeavors. Every painting, drawing or sculpture is a product of the context in which it was created: the political and social environment, the artist’s relationship with other artists, religious ideas, market pressures, and the prevailing philosophies in the art world.

This idea of context radically reshaped Chen’s approach to art. For her senior thesis exhibition, she decided to combine a painting with an installation that would provide context about related labor and migration issues. Her project focuses on the stories of Chinese immigrants who built the railroads of the American west in the 19th century.

Chen’s painting is based on a photo her mother took late at night of a mother and daughter waiting on a train platform in China. The photo was taken recently, but Chen’s painting has a timeless quality, and the assemblage of vellum invites guests to imagine them as 19th-century immigrant railroad workers. Chen calls the process of superimposing the railroad maps and identification documents onto vellum “making a portrait without figuratively portraying” the Chinese workers. In the transparent paper she is bringing visibility to the multilayered identities of people who were marginalized and whose lives were poorly documented.

Until last year, Chen was planning to study art history in graduate school. But then, in summer 2020, a Trump administration policy made international students enrolled exclusively in online courses — the only option at many universities during the pandemic — subject to deportation. The policy was later rescinded, but Chen realized that while art was powerful, she needed more practical tools to advocate for members of minority groups and immigrants. She started law school this fall at American University Washington College of Law, located in Washington, D.C. — a school recommended by her mentor, Brantl.

A career in law offers Chen the chance to work on behalf of underrepresented communities. She could pursue poverty law, intellectual property, or environmental and cultural preservation, such as cultural repatriation, the return of looted cultural artifacts to their country of origin. Although, as a first-year law student, she hasn’t yet chosen a focus, her career will be shaped by her personal missions: To be responsible. To live lightly on the earth, avoiding overconsumption. Ultimately, she wishes to give back to people who helped her, like her mother, her friends in West Texas, Professor of Art Hollis Hammonds and other faculty in the Visual Studies Department, and many other professors who guided her journey at St. Edward’s.

“I want to do law because I have to learn the system in order to change it,” Chen says. “Through my art and my writings, my research, and my future legal works, I want to change life for the better for people around me.”

Photos provided by Murphy Yanbing Chen

Portrait & Video of Murphy Chen by Chelsea Purgahn